What Was The Problem Was Cameras In 1800

The history of photography began in remote antiquity with the discovery of two critical principles: camera obscura image project and the observation that some substances are visibly altered past exposure to light. At that place are no artifacts or descriptions that betoken any attempt to capture images with light sensitive materials prior to the 18th century.

Around 1717, Johann Heinrich Schulze captured cut-out letters on a canteen of a light-sensitive slurry, simply he evidently never thought of making the results durable. Around 1800, Thomas Wedgwood made the first reliably documented, although unsuccessful effort at capturing camera images in permanent form. His experiments did produce detailed photograms, but Wedgwood and his associate Humphry Davy found no way to fix these images.

In the mid-1820s, Nicéphore Niépce first managed to gear up an epitome that was captured with a camera, only at least eight hours or even several days of exposure in the photographic camera were required and the primeval results were very crude. Niépce'south acquaintance Louis Daguerre went on to develop the daguerreotype process, the starting time publicly announced and commercially feasible photographic process. The daguerreotype required but minutes of exposure in the camera, and produced clear, finely detailed results. The details were introduced to the world in 1839, a engagement mostly accepted as the birth year of applied photography.[2] [3] The metal-based daguerreotype procedure shortly had some competition from the paper-based calotype negative and salt print processes invented by William Henry Fox Talbot and demonstrated in 1839 before long after news about the daguerreotype reached Talbot. Subsequent innovations fabricated photography easier and more than versatile. New materials reduced the required camera exposure time from minutes to seconds, and eventually to a small fraction of a 2nd; new photographic media were more than economical, sensitive or convenient. Since the 1850s, the collodion process with its glass-based photographic plates combined the loftier quality known from the Daguerreotype with the multiple impress options known from the calotype and was commonly used for decades. Roll films popularized casual apply by amateurs. In the mid-20th century, developments fabricated it possible for amateurs to take pictures in natural colour also as in black-and-white.

The commercial introduction of computer-based electronic digital cameras in the 1990s soon revolutionized photography. During the first decade of the 21st century, traditional movie-based photochemical methods were increasingly marginalized as the practical advantages of the new applied science became widely appreciated and the paradigm quality of moderately priced digital cameras was continually improved. Especially since cameras became a standard characteristic on smartphones, taking pictures (and instantly publishing them online) has become a ubiquitous everyday practice around the world.

Etymology [edit]

The coining of the word "photography" is usually attributed to Sir John Herschel in 1839. It is based on the Greek φῶς (phōs; genitive phōtos), meaning "light", and γραφή (graphê), meaning "drawing, writing", together meaning "drawing with light".[4]

Early history of the camera [edit]

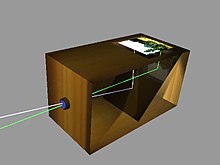

Principle of a box photographic camera obscura with mirror

A natural phenomenon, known equally camera obscura or pinhole prototype, can project a (reversed) prototype through a small opening onto an opposite surface. This principle may have been known and used in prehistoric times. The earliest known written record of the photographic camera obscura is to be found in Chinese writings by Mozi, dated to the fourth century BCE.[v] Until the 16th century the photographic camera obscura was mainly used to written report optics and astronomy, peculiarly to safely watch solar eclipses without dissentious the eyes. In the afterwards one-half of the 16th century some technical improvements were developed: a biconvex lens in the opening (start described by Gerolamo Cardano in 1550) and a diaphragm restricting the aperture (Daniel Barbaro in 1568) gave a brighter and sharper image. In 1558 Giambattista della Porta advised using the photographic camera obscura as a cartoon help in his popular and influential books. Della Porta'southward advice was widely adopted past artists and since the 17th century portable versions of the camera obscura were commonly used — showtime equally a tent, later equally boxes. The box type camera obscura was the footing for the earliest photographic cameras when photography was developed in the early on 19th century.[6]

Before 1700: Light sensitive materials [edit]

The notion that calorie-free can affect various substances — for instance, the sun tanning of skin or fading of textile — must have been around since very early times. Ideas of fixing the images seen in mirrors or other ways of creating images automatically may too have been in people'due south minds long before anything similar photography was developed.[vii] However, there seem to be no historical records of whatsoever ideas even remotely resembling photography before 1700, despite early on knowledge of light-sensitive materials and the camera obscura.[eight]

In 1614 Angelo Sala noted that[9] sunlight will plow powdered silver nitrate black, and that paper wrapped around silverish nitrate for a year will turn black.[10]

Wilhelm Homberg described how light darkened some chemicals in 1694.[11]

1700 to 1802: primeval concepts and fleeting photogram results [edit]

Schulze's Scotophors: earliest fleeting letter photograms (circa 1717) [edit]

Around 1717,[12] German language polymath Johann Heinrich Schulze accidentally discovered that a slurry of chalk and nitric acid into which some silvery particles had been dissolved was darkened by sunlight. Later on experiments with threads that had created lines on the bottled substance after he placed it in direct sunlight for a while, he applied stencils of words to the bottle. The stencils produced copies of the text in dark red, most violet characters on the surface of the otherwise whitish contents. The impressions persisted until they were erased by shaking the canteen or until overall exposure to lite obliterated them. Schulze named the substance "Scotophors" when he published his findings in 1719. He thought the discovery could be applied to observe whether metals or minerals contained any silver and hoped that farther experimentation past others would lead to some other useful results.[xiii] [fourteen] Schulze'south process resembled later photogram techniques and is sometimes regarded every bit the very first form of photography.[15]

De la Roche'south fictional image capturing procedure (1760) [edit]

The early on science fiction novel Giphantie [xvi] (1760) past the Frenchman Tiphaigne de la Roche described something quite like to (color) photography, a process that fixes fleeting images formed past rays of light: "They coat a piece of canvas with this textile, and identify it in front of the object to capture. The offset effect of this cloth is like to that of a mirror, but by ways of its viscous nature the prepared canvass, as is not the case with the mirror, retains a facsimile of the image. The mirror represents images faithfully, but retains none; our canvas reflects them no less faithfully, just retains them all. This impression of the image is instantaneous. The sail is and so removed and deposited in a dark place. An hour subsequently the impression is dry, and you lot have a movie the more than precious in that no art can imitate its truthfulness."[17] De la Roche thus imagined a process that made employ of a special substance in combination with the qualities of a mirror, rather than the camera obscura. The hour of drying in a dark place suggests that he perchance idea near the light sensitivity of the material, just he attributed the effect to its sticky nature.

Scheele's forgotten chemical fixer (1777) [edit]

In 1777, the pharmacist Carl Wilhelm Scheele was studying the more intrinsically lite-sensitive silvery chloride and determined that light darkened information technology by disintegrating information technology into microscopic dark particles of metallic argent. Of greater potential usefulness, Scheele institute that ammonia dissolved the silver chloride, merely not the night particles. This discovery could have been used to stabilize or "gear up" a photographic camera image captured with silver chloride, but was non picked upwards past the earliest photography experimenters.[xviii]

Scheele besides noted that scarlet light did non have much effect on silverish chloride, a phenomenon that would afterwards be applied in photographic darkrooms every bit a method of seeing black-and-white prints without harming their evolution.[19]

Although Thomas Wedgwood felt inspired past Scheele's writings in general, he must have missed or forgotten these experiments; he found no method to fix the photogram and shadow images he managed to capture around 1800 (see below).[19]

Elizabeth Fulhame and the effect of calorie-free on silver salts (1794) [edit]

Elizabeth Fulhame'due south book An essay on combustion [xx] described her experiments of the effects of light on silverish salts. She is improve known for her discovery of what is now called catalysis, but Larry J. Schaaf in his history of photography[21] [22] considered her work on silvery chemistry to correspond a major step in the development of photography.

Thomas Wedgwood and Humphry Davy: Fleeting detailed photograms (1790?–1802) [edit]

English lensman and inventor Thomas Wedgwood is believed to have been the first person to have thought of creating permanent pictures by capturing camera images on material coated with a light-sensitive chemical. He originally wanted to capture the images of a camera obscura, but found they were too faint to have an issue upon the silver nitrate solution that was recommended to him as a light-sensitive substance. Wedgwood did manage to copy painted glass plates and captured shadows on white leather, as well as on newspaper moistened with a argent nitrate solution. Attempts to preserve the results with their "distinct tints of brown or black, sensibly differing in intensity" failed. It is unclear when Wedgwood's experiments took identify. He may have started before 1790; James Watt wrote a letter to Thomas Wedgwood's father Josiah Wedgwood to thank him "for your instructions as to the Silverish Pictures, nigh which, when at home, I will brand some experiments". This letter (now lost) is believed to accept been written in 1790, 1791 or 1799. In 1802, an account by Humphry Davy detailing Wedgwood'southward experiments was published in an early journal of the Royal Establishment with the title An Account of a Method of Copying Paintings upon Drinking glass, and of Making Profiles, by the Agency of Lite upon Nitrate of Silver. Davy added that the method could be used for objects that are partly opaque and partly transparent to create authentic representations of, for instance, "the woody fibres of leaves and the wings of insects". He too found that solar microscope images of small objects were easily captured on prepared paper. Davy, apparently unaware or forgetful of Scheele's discovery, ended that substances should be found to eliminate (or deactivate) the unexposed particles in silver nitrate or silver chloride "to return the process as useful as it is elegant".[nineteen] Wedgwood may accept prematurely abandoned his experiments because of his delicate and failing wellness. He died at age 34 in 1805.

Davy seems not to have connected the experiments. Although the journal of the nascent Regal Institution probably reached its very small group of members, the commodity must have been read eventually by many more people. It was reviewed by David Brewster in the Edinburgh Magazine in December 1802, appeared in chemistry textbooks as early on every bit 1803, was translated into French and was published in German in 1811. Readers of the commodity may have been discouraged to discover a fixer, considering the highly acclaimed scientist Davy had already tried and failed. Apparently the article was non noted by Niépce or Daguerre, and by Talbot simply after he had developed his own processes.[19] [23]

Jacques Charles: Fleeting silhouette photograms (circa 1801?) [edit]

French balloonist, professor and inventor Jacques Charles is believed to have captured fleeting negative photograms of silhouettes on low-cal-sensitive paper at the start of the 19th century, prior to Wedgwood. Charles died in 1823 without having documented the process, but purportedly demonstrated it in his lectures at the Louvre. It was non publicized until François Arago mentioned it at his introduction of the details of the daguerreotype to the earth in 1839. He afterward wrote that the beginning idea of fixing the images of the camera obscura or the solar microscope with chemical substances belonged to Charles. Later historians probably but built on Arago's information, and, much later, the unsupported year 1780 was fastened to it.[24] Equally Arago indicated the first years of the 19th century and a date prior to the 1802 publication of Wedgwood'south process, this would mean that Charles' demonstrations took identify in 1800 or 1801, assuming that Arago was this accurate almost forty years afterward.

1816 to 1833: Niépce's earliest fixed images [edit]

The primeval known surviving heliographic engraving, made in 1825. Information technology was printed from a metal plate made by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce with his "heliographic procedure".[25] The plate was exposed under an ordinary engraving and copied it past photographic means. This was a step towards the first permanent photo from nature taken with a camera obscura.

The Boulevard du Temple, a daguerreotype fabricated past Louis Daguerre in 1838, is generally accepted as the earliest photograph to include people. It is a view of a busy street, but because the exposure lasted for several minutes the moving traffic left no trace. Only the two men nearly the bottom left corner, i of them apparently having his boots polished by the other, remained in i place long plenty to be visible.

In 1816, Nicéphore Niépce, using newspaper coated with silverish chloride, succeeded in photographing the images formed in a pocket-size camera, but the photographs were negatives, darkest where the camera image was lightest and vice versa, and they were not permanent in the sense of existence reasonably lite-fast; similar before experimenters, Niépce could discover no mode to prevent the blanket from darkening all over when it was exposed to light for viewing. Disenchanted with silverish salts, he turned his attention to light-sensitive organic substances.[26]

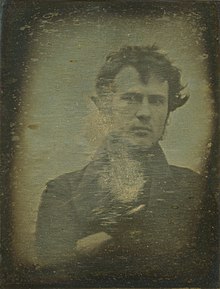

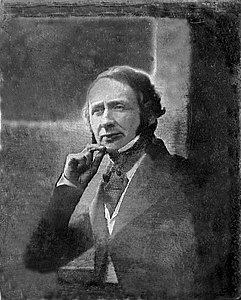

Robert Cornelius, self-portrait, Oct or November 1839, an approximately quarter plate size daguerreotype. On the back is written, "The first light picture e'er taken".

I of the oldest photographic portraits known, 1839 or 1840,[27] made past John William Draper of his sister, Dorothy Catherine Draper

Daguerreotype Of Dr John William Draper at NYU in the fall of 1839, sitting with his found experiment and pen in paw. Possibly past Samuel Morse.

The oldest surviving photograph of the image formed in a camera was created by Niépce in 1826 or 1827.[2] It was made on a polished sheet of pewter and the low-cal-sensitive substance was a thin coating of bitumen, a naturally occurring petroleum tar, which was dissolved in lavander oil, applied to the surface of the pewter and allowed to dry before use.[28] Later on a very long exposure in the photographic camera (traditionally said to exist eight hours, just now believed to be several days),[29] the bitumen was sufficiently hardened in proportion to its exposure to light that the unhardened office could be removed with a solvent, leaving a positive prototype with the light areas represented by hardened bitumen and the dark areas by blank pewter.[28] To see the prototype plainly, the plate had to exist lit and viewed in such a way that the blank metal appeared dark and the bitumen relatively light.[26]

In partnership, Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône and Louis Daguerre in Paris refined the bitumen process,[30] substituting a more sensitive resin and a very different post-exposure treatment that yielded college-quality and more easily viewed images. Exposure times in the camera, although substantially reduced, were yet measured in hours.[26]

1832 to 1840: early monochrome processes [edit]

Niépce died suddenly in 1833, leaving his notes to Daguerre. More interested in silver-based processes than Niépce had been, Daguerre experimented with photographing camera images directly onto a mirror-similar silverish-surfaced plate that had been fumed with iodine vapor, which reacted with the argent to form a coating of silver iodide. As with the bitumen procedure, the result appeared equally a positive when information technology was suitably lit and viewed. Exposure times were still impractically long until Daguerre fabricated the pivotal discovery that an invisibly slight or "latent" paradigm produced on such a plate by a much shorter exposure could be "developed" to full visibility past mercury fumes. This brought the required exposure time down to a few minutes under optimum conditions. A stiff hot solution of mutual salt served to stabilize or fix the image by removing the remaining silver iodide. On 7 January 1839, this starting time consummate practical photographic process was announced at a coming together of the French Academy of Sciences,[31] and the news quickly spread.[32] At first, all details of the process were withheld and specimens were shown merely at Daguerre's studio, under his shut supervision, to Academy members and other distinguished guests.[33] Arrangements were fabricated for the French government to buy the rights in exchange for pensions for Niépce'due south son and Daguerre and present the invention to the world (with the exception of Smashing Uk, where an agent for Daguerre patented it) as a gratuitous gift.[34] Complete instructions were fabricated public on 19 August 1839.[35] Known as the daguerreotype process, it was the almost mutual commercial procedure until the late 1850s when it was superseded by the collodion process.

French-built-in Hércules Florence developed his own photographic technique in 1832 or 1833 in Brazil, with some help of pharmacist Joaquim Corrêa de Mello (1816–1877). Looking for some other method to copy graphic designs he captured their images on paper treated with silver nitrate equally contact prints or in a camera obscura device. He did not manage to properly set up his images and abandoned the project after hearing of the Daguerreotype procedure in 1839[36] and didn't properly publish any of his findings. He reportedly referred to the technique as "photographie" (in French) as early as 1833, also helped past a suggestion of De Mello.[37] Some extant photographic contact prints are believed to have been fabricated in circa 1833 and kept in the collection of IMS.

Henry Fox Talbot had already succeeded in creating stabilized photographic negatives on newspaper in 1835, simply worked on perfecting his own process after reading early reports of Daguerre's invention. In early 1839, he caused a key improvement, an effective logroller, from his friend John Herschel, a polymath scientist who had previously shown that hyposulfite of soda (commonly called "hypo" and now known formally every bit sodium thiosulfate) would dissolve silverish salts.[38] News of this solvent also benefited Daguerre, who soon adopted it as a more efficient alternative to his original hot salt water method.[39]

Talbot's early silver chloride "sensitive newspaper" experiments required photographic camera exposures of an hour or more than. In 1841, Talbot invented the calotype process, which, like Daguerre's process, used the principle of chemical development of a faint or invisible "latent" image to reduce the exposure fourth dimension to a few minutes. Paper with a coating of silver iodide was exposed in the camera and adult into a translucent negative image. Unlike a daguerreotype, which could only be copied past photographing it with a camera, a calotype negative could be used to make a large number of positive prints by simple contact printing. The calotype had yet another stardom compared to other early photographic processes, in that the finished production lacked fine clarity due to its translucent paper negative. This was seen as a positive attribute for portraits because it softened the appearance of the human being face[ citation needed ]. Talbot patented this process,[xl] which profoundly limited its adoption, and spent many years pressing lawsuits against alleged infringers. He attempted to enforce a very wide interpretation of his patent, earning himself the ill will of photographers who were using the related glass-based processes later introduced by other inventors, but he was eventually defeated. All the same, Talbot'due south developed-out silver halide negative process is the bones engineering science used by chemical film cameras today. Hippolyte Bayard had also developed a method of photography but delayed announcing it, and and then was not recognized every bit its inventor.

In 1839, John Herschel fabricated the starting time drinking glass negative, only his process was difficult to reproduce. Slovene Janez Puhar invented a process for making photographs on glass in 1841; information technology was recognized on June 17, 1852 in Paris by the Académie National Agricole, Manufacturière et Commerciale.[41] In 1847, Nicephore Niépce's cousin, the pharmacist Niépce St. Victor, published his invention of a process for making glass plates with an albumen emulsion; the Langenheim brothers of Philadelphia and John Whipple and William Brood Jones of Boston also invented workable negative-on-drinking glass processes in the mid-1840s.[42]

1850 to 1900 [edit]

In 1851, English language sculptor Frederick Scott Archer invented the collodion process.[43] Photographer and children's author Lewis Carroll used this process. (Carroll refers to the process as "Talbotype" in the story "A Photographer'southward Twenty-four hour period Out".)[44]

Herbert Bowyer Berkeley experimented with his own version of collodion emulsions later on Samman introduced the thought of adding dithionite to the pyrogallol programmer.[ commendation needed ] Berkeley discovered that with his own improver of sulfite, to absorb the sulfur dioxide given off by the chemic dithionite in the developer, dithionite was not required in the developing procedure. In 1881, he published his discovery. Berkeley's formula contained pyrogallol, sulfite, and citric acrid. Ammonia was added just earlier use to make the formula alkaline. The new formula was sold past the Platinotype Company in London as Sulphur-Pyrogallol Programmer.[45]

Nineteenth-century experimentation with photographic processes frequently became proprietary. The German language-built-in, New Orleans photographer Theodore Lilienthal successfully sought legal redress in an 1881 infringement case involving his "Lambert Procedure" in the Eastern District of Louisiana.

-

Roger Fenton'due south assistant seated on Fenton'due south photographic van, Crimea, 1855

-

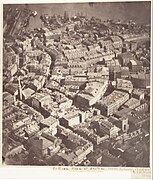

Boston, as the Eagle and the Wild Goose See It, by J.Due west. Black, the first recorded aerial photo, 1860

-

The 1866 "Jumelle de Nicour", an early on attempt at a small-format, portable camera

Popularization [edit]

The daguerreotype proved pop in response to the demand for portraiture that emerged from the centre classes during the Industrial Revolution.[46] [ citation needed ] This demand, which could not exist met in volume and in cost by oil painting, added to the push button for the evolution of photography.

Roger Fenton and Philip Henry Delamotte helped popularize the new mode of recording events, the first by his Crimean War pictures, the second by his record of the disassembly and reconstruction of The Crystal Palace in London. Other mid-nineteenth-century photographers established the medium equally a more precise means than engraving or lithography of making a record of landscapes and architecture: for example, Robert Macpherson'southward wide range of photographs of Rome, the interior of the Vatican, and the surrounding countryside became a sophisticated tourist'southward visual tape of his own travels.

In 1839, François Arago reported the invention of photography to stunned listeners by displaying the commencement photograph taken in Egypt; that of Ras El Tin Palace.[47]

In America, by 1851 a broadsheet by daguerreotypist Augustus Washington was advertising prices ranging from 50 cents to $10.[48] However, daguerreotypes were fragile and hard to copy. Photographers encouraged chemists to refine the process of making many copies cheaply, which eventually led them back to Talbot's process.

Ultimately, the photographic process came well-nigh from a series of refinements and improvements in the first 20 years. In 1884 George Eastman, of Rochester, New York, adult dry out gel on paper, or film, to supersede the photographic plate and then that a photographer no longer needed to deport boxes of plates and toxic chemicals effectually. In July 1888 Eastman's Kodak camera went on the market with the slogan "You press the push, nosotros do the rest".[50] Now anyone could accept a photograph and exit the complex parts of the process to others, and photography became bachelor for the mass-market in 1901 with the introduction of the Kodak Brownie.

-

-

A mid-19th century "Brady stand up" armrest table, used to help subjects keep still during long exposures. It was named for famous U.s. photographer Mathew Brady.

-

An 1855 Punch cartoon satirized problems with posing for Daguerreotypes: slight movement during exposure resulted in blurred features, red-blindness made rosy complexions wait dark.

-

In this 1893 multiple-exposure play tricks photo, the lensman appears to exist photographing himself. Information technology satirizes studio equipment and procedures that were nearly obsolete past then. Note the clamp to concur the sitter'southward head nonetheless.

-

A comparison of common print sizes used in photographic studios during the 19th century. Sizes are in inches.

Stereoscopic photography [edit]

Charles Wheatstone developed his mirror stereoscope around 1832, but did not really publicize his invention until June 1838. He recognized the possibility of a combination with photography before long subsequently Daguerre and Talbot announced their inventions and got Henry Fox Talbot to produce some calotype pairs for the stereoscope. He received the first results in Oct 1840, but was non fully satisfied as the bending betwixt the shots was very large. Between 1841 and 1842 Henry Collen made calotypes of statues, buildings and portraits, including a portrait of Charles Babbage shot in Baronial 1841. Wheatstone also obtained daguerreotype stereograms from Mr. Bristles in 1841 and from Hippolyte Fizeau and Antoine Claudet in 1842. None of these have yet been located.[51]

David Brewster developed a stereoscope with lenses and a binocular camera in 1844. He presented two stereoscopic cocky portraits made by John Adamson in March 1849.[52] A stereoscopic portrait of Adamson in the Academy of St Andrews Library Photographic Archive, dated "circa 1845', may exist one of these sets.[51] A stereoscopic daguerreotype portrait of Michael Faraday in Kingston College'southward Wheatstone collection and on loan to Bradford National Media Museum, dated "circa 1848", may be older.[53]

Color process [edit]

A practical means of color photography was sought from the very outset. Results were demonstrated by Edmond Becquerel as early every bit the twelvemonth of 1848, merely exposures lasting for hours or days were required and the captured colors were so light-sensitive they would just bear very cursory inspection in dim calorie-free.

The first durable colour photograph was a prepare of three black-and-white photographs taken through reddish, greenish, and blueish colour filters and shown superimposed by using three projectors with similar filters. Information technology was taken by Thomas Sutton in 1861 for apply in a lecture by the Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell, who had proposed the method in 1855.[54] The photographic emulsions so in use were insensitive to well-nigh of the spectrum, and so the result was very imperfect and the demonstration was before long forgotten. Maxwell's method is at present most widely known through the early 20th century work of Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii. It was made practical by Hermann Wilhelm Vogel's 1873 discovery of a manner to make emulsions sensitive to the rest of the spectrum, gradually introduced into commercial utilise beginning in the mid-1880s.

Ii French inventors, Louis Ducos du Hauron and Charles Cros, working unknown to each other during the 1860s, famously unveiled their nearly identical ideas on the same day in 1869. Included were methods for viewing a set of three colour-filtered black-and-white photographs in color without having to projection them, and for using them to fill-color prints on paper.[55]

The first widely used method of color photography was the Autochrome plate, a process inventors and brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière began working on in the 1890s and commercially introduced in 1907.[56] It was based on one of Louis Duclos du Haroun's ideas: instead of taking three separate photographs through color filters, take one through a mosaic of tiny color filters overlaid on the emulsion and view the results through an identical mosaic. If the private filter elements were small enough, the three primary colors of red, blueish, and greenish would alloy together in the eye and produce the aforementioned additive colour synthesis as the filtered projection of iii separate photographs.

Autochrome plates had an integral mosaic filter layer with roughly five million previously dyed potato grains per square inch added to the surface. Then through the employ of a rolling press, five tons of pressure level were used to flatten the grains, enabling every one of them to capture and absorb colour and their microscopic size allowing the illusion that the colors are merged. The last step was adding a glaze of the light-capturing substance silver bromide, after which a color paradigm could be imprinted and developed. In order to see information technology, reversal processing was used to develop each plate into a transparent positive that could be viewed direct or projected with an ordinary projector. Ane of the drawbacks of the engineering was an exposure time of at least a second in brilliant daylight, with the time required rapidly increasing in poor low-cal. An indoor portrait required several minutes with the subject stationary. This was because the grains absorbed colour adequately slowly, and a filter of a yellowish-orangish color was required to proceed the photograph from coming out excessively blue. Although necessary, the filter had the effect of reducing the amount of light that was captivated. Another drawback was that the image could but be enlarged so much earlier the many dots that made up the paradigm would become credible.[56] [57]

Competing screen plate products soon appeared, and motion picture-based versions were eventually made. All were expensive, and until the 1930s none was "fast" plenty for manus-held snapshot-taking, and so they mostly served a niche market of affluent advanced amateurs.

A new era in color photography began with the introduction of Kodachrome film, available for 16 mm home movies in 1935 and 35 mm slides in 1936. It captured the blood-red, green, and blue colour components in iii layers of emulsion. A circuitous processing functioning produced complementary cyan, magenta, and yellow dye images in those layers, resulting in a subtractive color image. Maxwell's method of taking three separate filtered black-and-white photographs continued to serve special purposes into the 1950s and beyond, and Polachrome, an "instant" slide film that used the Autochrome'due south condiment principle, was bachelor until 2003, but the few color print and slide films still existence made in 2015 all use the multilayer emulsion approach pioneered by Kodachrome.

-

The first durable colour photo, taken by Thomas Sutton in 1861.

Development of digital photography [edit]

Walden Kirsch as scanned into the SEAC computer in 1957

In 1957, a squad led past Russell A. Kirsch at the National Institute of Standards and Applied science developed a binary digital version of an existing technology, the wirephoto drum scanner, and then that alphanumeric characters, diagrams, photographs and other graphics could be transferred into digital computer memory. Ane of the first photographs scanned was a picture of Kirsch's infant son Walden. The resolution was 176x176 pixels with but one bit per pixel, i.e., stark blackness and white with no intermediate grayness tones, but by combining multiple scans of the photograph done with different black-white threshold settings, grayscale information could besides be acquired.[58]

The charge-coupled device (CCD) is the image-capturing optoelectronic component in first-generation digital cameras. It was invented in 1969 by Willard Boyle and George E. Smith at AT&T Bell Labs as a memory device. The lab was working on the Picturephone and on the development of semiconductor bubble memory. Merging these 2 initiatives, Boyle and Smith conceived of the design of what they termed "Charge 'Bubble' Devices". The essence of the design was the power to transfer charge along the surface of a semiconductor. Information technology was Dr. Michael Tompsett from Bell Labs however, who discovered that the CCD could exist used as an imaging sensor. The CCD has increasingly been replaced by the active pixel sensor (APS), commonly used in cell telephone cameras. These mobile phone cameras are used by billions of people worldwide, dramatically increasing photographic activeness and material and besides fueling citizen journalism.

- 1973 – Fairchild Semiconductor releases the first large image-capturing CCD fleck: 100 rows and 100 columns.[59]

- 1975 – Bryce Bayer of Kodak develops the Bayer filter mosaic design for CCD color paradigm sensors

- 1986 – Kodak scientists develop the world'south commencement megapixel sensor.

The web has been a popular medium for storing and sharing photos always since the first photograph was published on the web by Tim Berners-Lee in 1992 (an paradigm of the CERN house band Les Horribles Cernettes). Since so sites and apps such as Facebook, Flickr, Instagram, Picasa (discontinued in 2016), Imgur, Photobucket and Snapchat take been used by many millions of people to share their pictures.

Gallery of historical photos [edit]

-

Small-scale Wooden box containing uncased archaic daguerreotypes. They are the early work of Dr John Draper and Samuel Morse at NYU in the fall of 1839. A failed image attempt and four expert images from the box are posted in this gallery.

-

Failed image attempt by John W Draper from the box containing his early on efforts at making daguerreotypes at NYU in the fall of 1839

-

Dr John William Draper, long credited as the showtime person to have an epitome of the human being face, sitting with his plant experiment , pen in mitt, at NYU in the autumn of 1839. Daguerreotype past Samuel Morse 1839.

-

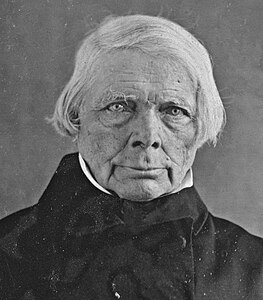

Samuel Morse, Art Professor at NYU in 1839. Daguerreotype by Dr John William Draper 1839.

-

Dr Martyn Paine. One Of the founders Of the NYU medical school Daguerreotype by Dr John William Draper 1839.

-

-

-

-

Conrad Heyer at historic period 103 in 1852, possibly the earliest-built-in American e'er photographed (born 1749)

-

Run into also [edit]

- History of the camera

- History of Photography (academic journal)

- Albumen print

- History of photographic lens design

- Timeline of photography technology

- Outline of photography

- Photography past indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Women photographers

- Moving-picture show camera

- Instant pic

References [edit]

- ^ "The First Photograph". www.hrc.utexas.edu . Retrieved four April 2020.

- ^ a b Hirsch, Robert (2 June 2018). Seizing the Light: A History of Photography. McGraw-Colina. ISBN9780697143617 – via Google Books.

- ^ The Michigan Technic 1882 The Genesis of Photography with Hints on Developing

- ^ "photography - Search Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- ^ "Did Yous Know? This is the Starting time-ever Photograph of Human Captured on a Camera". News18 . Retrieved nineteen August 2020.

- ^ Jade (20 May 2019). "The History of the Camera". History Things . Retrieved xix August 2020.

- ^ Gernsheim, Helmut (1986). A concise history of photography. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-25128-four

- ^ Batchen (1999). Burning with Want: The Conception of Photography. ISBN9780262522595.

- ^ "Septem planetarum terrestrium spagirica recensio. Qua perspicue declaratur ratio nominis Hermetici, analogia metallorum cum microcosmo, ..." apud Wilh. Janssonium. 2 June 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Eder, Josef Maria (1932). Geschichte der Photographie [History of Photography]. p. 32.

- ^ Sloane, Thomas O'Conor (1895). Facts Worth Knowing Selected Mainly from the Scientific American for Household, Workshop, and Farm Embracing Practical and Useful Information for Every Branch of Industry. S. S. Scranton and Company.

- ^ The title page dated 1719 of a section (of a 1721 volume) containing the original publication tin can be seen here. In the text Schulze claims he did the experiment ii years earlier

- ^ Bibliotheca Novissima Oberservationum ac Recensionum (in Latin). 1721. pp. 234–240.

- ^ Litchfield, Richard Buckley (1903). Tom Wedgwood, the Starting time Lensman, etc., London, Duckworth and Co. Out of copyright and available gratis at archive.org. In Appendix A (pp. 217-227), Litchfield evaluates assertions that Schulze's experiments should exist chosen photography and includes a complete English translation (from the original Latin) of Schulze's 1719 account of them as reprinted in 1727.

- ^ Susan Watt (2003). Silver. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 21–. ISBN978-0-7614-1464-three . Retrieved 28 July 2013.

... But the first person to utilise this belongings to produce a photographic image was High german physicist Johann Heinrich Schulze.

- ^ de la Roche, Tiphaigne (1760). Giphantie (in French).

- ^ "Tiphaigne de la Roche – Giphantie,1760". wordpress.com. vii July 2015.

- ^ "Carl Wilhelm Scheele | Biography, Discoveries, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d Litchfield, Richard Buckley (1903). Tom Wedgwood, the Beginning Lensman. Duckworth and Co. pp. 185–205.

- ^ Fulhame, Elizabeth (1794). An essay on combustion, with a view to a new art of dying and painting. Wherein the phlogistic and antiphlogistic hypotheses are proven erroneous. London: Printed for the author, by J. Cooper. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Schaaf, Larry J. (1990). "The first fifty years of British photography, 1794-1844". In Pritchard, Michael (ed.). Technology and art: the birth and early years of photography: the proceedings of the Royal Photographic Historical Grouping briefing 1-3 September 1989. Bath: RPS Historical Group. pp. 9–18. ISBN9780951532201.

- ^ Schaaf, Larry J. (1992). Out of the shadows: Herschel, Talbot, & the invention of photography. New Oasis: Yale University Printing. pp. 23–25. ISBN9780300057058.

- ^ Batchen, Geoffrey (1999). Burning with Desire: The Formulation of Photography. MIT Printing.

- ^ Litchfield, Richard Buckley (1903). Tom Wedgwood, the Offset Photographer - Appendix B. Duckworth and Co. pp. 228–240.

- ^ "The First Photograph — Heliography". Archived from the original on six Oct 2009. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

from Helmut Gernsheim'due south commodity, "The 150th Anniversary of Photography," in History of Photography, Vol. I, No. 1, Jan 1977: ...In 1822, Niépce coated a glass plate... The sunlight passing through... This first permanent example... was destroyed... some years afterwards.

- ^ a b c "Nicéphore Niépce Business firm Museum inventor of photography - Nicephore Niepce House Photo Museum". www.niepce.org.

- ^ Folpe, Emily Kies (2002). It Happened on Washington Square. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 94. ISBN0-8018-7088-7.

- ^ a b [1] By Christine Sutton

- ^ Niépce House Museum: Invention of Photography, Function three. Retrieved 25 May 2013. The traditional judge of eight or nine hours originated in the 1950s and is based mainly on the fact that sunlight strikes the buildings as if from an arc across the sky, an effect which several days of continuous exposure would besides produce.

- ^ "Daguerre (1787–1851) and the Invention of Photography". Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Oct 2004. Retrieved 6 May 2008.

- ^ (Arago, François) (1839) "Fixation des images qui se forment au lobby d'une chambre obscure" (Fixing of images formed at the focus of a camera obscura), Comptes rendus, 8 : four-7.

- ^ By mid-Feb successful attempts to replicate "Chiliad. Daguerre's cute discovery", using chemicals on newspaper, had already taken identify in Deutschland and England: The Times (London), 21 February 1839, p.6.

- ^ due east.yard., a ix May 1839 showing to John Herschel, documented by Herschel'south letter to WHF Talbot. See the included footnote #1 (past Larry Schaaf?) for context. Accessed 11 September 2014.

- ^ Daguerre (1839), pages 1-4.

- ^ Run into:

- (Arago, François) (1839) "Le daguerreotype", Comptes rendus, ix : 250-267.

- Daguerre, Historique et description des procédés du daguerréotype et du diorama [History and clarification of the processes of the daguerreotype and diorama] (Paris, French republic: Alphonse Giroux et Cie., 1839).

- ^ "Cronologia de Hercule Florence". ims.com.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). ii June 2017.

- ^ Kossoy, Boris (xiv December 2017). The Pioneering Photographic Piece of work of Hercule Florence. ISBN9781315468952.

- ^ John F. W. Herschel (1839) "Annotation on the art of photography, or the application of the chemic rays of light to the purposes of pictorial representation," Proceedings of the Imperial Society of London, iv : 131-133. On folio 132 Herschel mentions the use of hyposulfite.

- ^ Daguerre, Historique et clarification des procédés du daguerréotype et du diorama [History and description of the processes of the daguerreotype and diorama] (Paris, France: Alphonse Giroux et Cie., 1839). On page 11, for example, Daguerre states: "Cette surabondance contribue à donner des tons roux, même en enlevant entièrement fifty'iode au moyen d'united nations lavage à l'hyposulfite de soude ou au sel marin." (This overabundance contributes towards giving red tones, even while completely removing the iodine by means of a rinse in sodium hyposulfite or in bounding main common salt.)

- ^ Comeback in photographic pictures, Henry Fox Talbot, United States Patent Role, patent no. 5171, June 26, 1847.

- ^ "Life and work of Janez Puhar | (accessed December xiii, 2009)".

- ^ Michael R. Peres (2007). The Focal encyclopedia of photography: digital imaging, theory and applications, history, and science. Focal Printing. p. 38. ISBN978-0-240-80740-9.

- ^ Richard G. Condon (1989). "The History and Development of Arctic Photography". Chill Anthropology. 26 (1): 52. JSTOR 40316177.

- ^ The Complete Works of Lewis Carroll. Random House Mod Library

- ^ Levenson, K. I. P (May 1993). "Berkeley, overlooked man of photo science". Photographic Journal. 133 (4): 169–71.

- ^ Gillespie, Sarah Kate (2016). The Early American Daguearreotype: Cross Currents in Art and Technology. Cambridge: Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN9780262034104.

- ^ Koehler, Jeff (2015). "Capturing the Light of the Nile". Saudi Aramco World. Vol. 66, no. vi. Aramco Services Company. pp. 16–23. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Loke, Margarett (7 July 2000). "Photography review; In a John Brown Portrait, The Essence of a Militant". The New York Times . Retrieved 16 March 2007.

- ^ Eric Hosking; Harold Lowes (1947), Masterpieces of Bird Photography, William Collins, Sons, p. 9, ASIN B000O8CPQK, Wikidata Q108533626

- ^ "History". Kodak-History . Retrieved 2021-12-04 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "First 3D photograph - the technology". benbeck.co.uk . Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ Belgique, Académie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de (1849). Bulletins de l'Académie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique (in French). Hayez.

- ^ "Stereoscopic Daguerreotype Portrait of Faraday | Science Museum Group Collection". collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk . Retrieved vii March 2020.

- ^ James Clerk Maxwell (2003). The Scientific Papers of James Clerk Maxwell. Courier Dover Publications. p. 449. ISBN0-486-49560-4.

- ^ Brian, Coe (1976). The Nascency of Photography. Ash & Grant. ISBN0-904069-07-9.

- ^ a b Douglas R. Nickel (1992). "Autochromes by Clarence H. White". Tape of the Art Museum, Princeton Academy. 2. 51 (2): 31–32. doi:10.2307/3774691. JSTOR 3774691.

- ^ "Potatoes to Pictures". The American Museum of Photography. The American Photography Museum.

- ^ "SEAC and the Start of Prototype Processing at the National Bureau of Standards – Earliest Image Processing". nist.gov. Archived from the original on nineteen July 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ Janesick, James R (2001). Scientific Charge Coupled Devices. SPIE Printing. ISBN0-8194-3698-4.

Further reading [edit]

- Hannavy, John. Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, 5 volumes

- Clerc, L.P. Photography Theory and Do, being an English language edition of "La Technique Photographique"

External links [edit]

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 845–522.

- The Silver Sheet: Daguerreotype Masterpieces from the J. Paul Getty Museum Bates Lowry, Isabel Barrett Lowry 1998

- A History of Photography from its Ancestry Till the 1920s past Dr. Robert Leggat, now hosted by Dr Michael Prichard

- The First Photo at The University of Texas at Austin

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_photography

Posted by: bryantheareather.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Was The Problem Was Cameras In 1800"

Post a Comment